A species saved, but still struggling

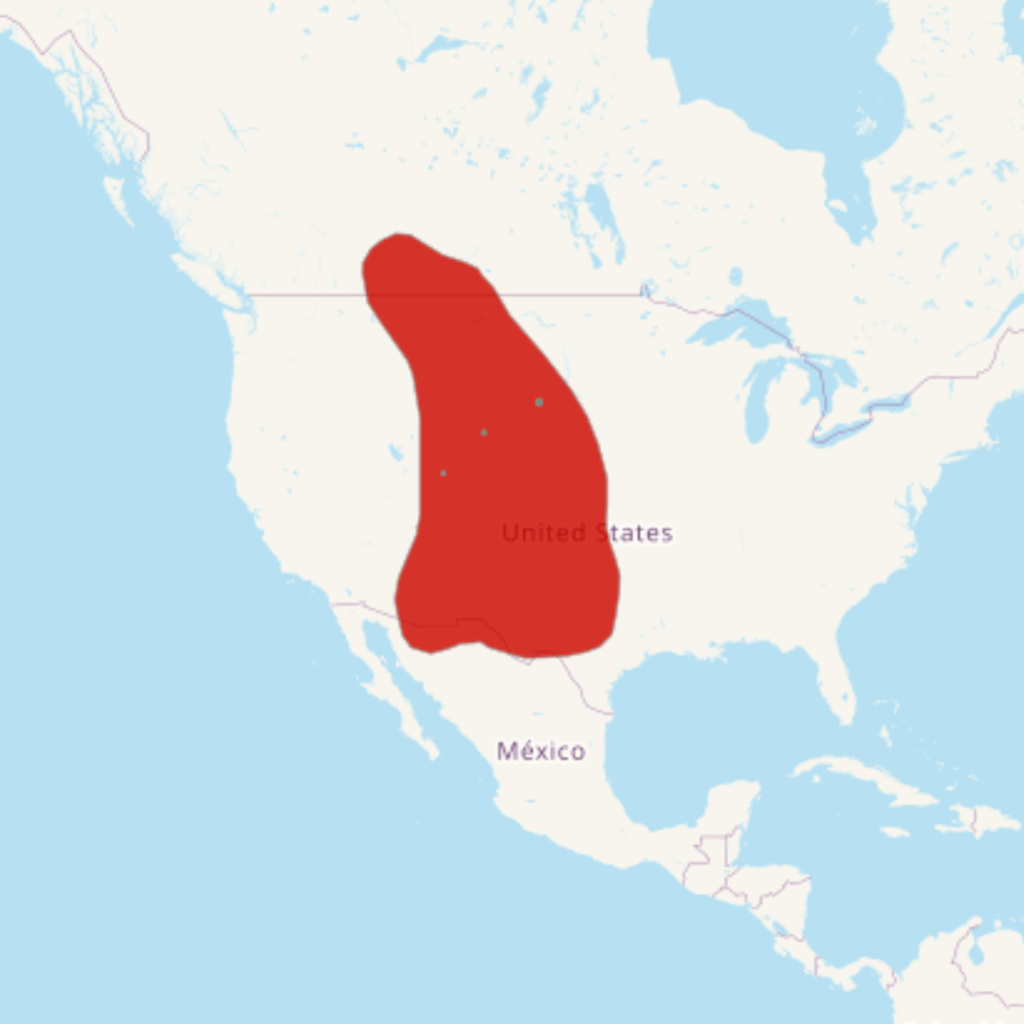

The black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes) was once a widespread small carnivore across North America’s Great Plains. Its historical range includes 12 US states, the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta, and the Mexican state of Chihuahua.

Presumed extinct in the late 1970s, a Wyoming population was rediscovered in 1981, which led to recovery efforts. Traditional captive breeding programmes and habitat protection have increased wild populations to an estimated 325 individuals across 13 sites, all descended from seven founders. However, wild populations have been stagnant for about a decade. The IUCN lists the species as Endangered.

Why is the black-footed ferret still endangered?

One of the main ongoing threats is the decline of prairie dogs (Cynomys spp.). Prairie dogs are the ferret’s primary food source and provide shelter, as black-footed ferrets live and raise their kits in old prairie dog burrows.

Additionally, the loss of contiguous shortgrass prairie habitat has isolated the remaining ferret populations. Black-footed ferrets currently occupy 300,000 acres of North America. To leave the endangered-species list, they would need about three times that area.

Further threats include sylvatic plague and reduced genetic fitness from inbreeding. Sylvatic plague, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and introduced to North America in the early 1900s, is the primary threat to reintroduced populations.